Making art is a uniquely human endeavour and an artist, the maker of art, is someone who distills what they feel and think about the world and expresses this visually. This requires one to read, to see, to listen, to feel, to question and be curious; to know, and yet to doubt; to have humility and to be brave.

William Kentridge does all this by creating ‘a safe space for uncertainty’, and his work instructs us in this.

All texts below are extracted from conversations and interviews with William Kentridge, or texts written by him.

READ

History as collage is an important way of understanding the world. A single narrative always comes from a single viewpoint and there are always other viewpoints. I am sceptical of the certainties which come with a single narrative of history.

Excerpt from Six Drawing Lessons (Drawing Lesson 5: In Praise of Mistranslation), 2012

SEE

What is it that we do when we see?

In Johannesburg, we have dry winters. In summer we have heat, and thunderstorms in the afternoons. Our sublime arrives in the form of huge cumulus nimbus clouds that pile themselves up over the city. With every day, when we have a storm, a new mountain range, a new Alps, is built for us again. In that way the mine dumps can exist, be erased, be rebuilt, so from a clear sky the cathedrals of clouds construct themselves. We see two things in the clouds. Shapes: a dog’s head, an old man’s face with protruding chin, the back of a head on a shoulder. This is not our ability to see things. It is not an act of generosity to see them. It is about not being able to stop ourselves from seeing the shapes. The man’s head comes to you. Once recognised, you cannot stop yourself from seeing it. This is one element of the clouds. The other is the changing itself, their shifting form, an awareness of the engine in the clouds. Lying on one’s back, looking at the clouds in the late afternoon, there is a seed of understanding that a child gets, of the nature of provisionality. Something is growing within, changing the outside form, becoming itself.

I’m interested in machines that make you aware of the process of seeing and aware of what you do when you construct the world by looking. This is interesting in itself, but more so as a broad-based metaphor for how we understand the world.

How much do we need to understand or know of the world, to understand? You have, for example, an assortment of torn paper shapes. They rearrange themselves in the form of a horse. Fragments leave the screen, reducing the horse until it is made up of four pieces of paper – a neck, a back, two legs.

Making a Horse, video fragment from studio work in progress, 2021

LISTEN

I film my eight year-old son. He takes a jar of paint, a handful of pencils, some books and papers. He throws the jar of paint over the wall, scatters the pencils, tears the papers and scatters the shards. We run the film in reverse – and there is utopian perfection. The papers construct themselves, perfectly, every time. He gathers them all. He catches twelve pencils, all arriving from different corners in the same moment. In the jar he catches all the paint, not a drop spilt. The wall is pristine. His joy at his own skill is overflowing. Can I do it again, he asks? Yes. But first we have to clean the studio, clean the paint off the wall, pick up the torn paper, gather the pencils.

Excerpt from performance of Refuse the Hour, Cape Town, South Africa, 2015

FEEL

To live with a tree for fifty years is a sign of privilege and surplus. To not need the tree for either wood or fire is a luxury. When I was nine years old we planted two white stinkwoods in the garden. All my childhood I waited for the trees to grow, to be strong enough to to hold a hammock. They refused. Twenty years later I returned to live in the house with my family and the trees were mature. Fifteen years later, the trees were magnificent. And then one of them was struck by lightning and died. The shock, not just the hole in the shade canopy, the gap in the garden, but rather the shaking of the belief that a tree is a gift for future generations or – if not for future generations – then at least for other people… its lifespan should be so much longer. How could the tree die before me? No. If the tree could die, how vulnerable are we or am I?

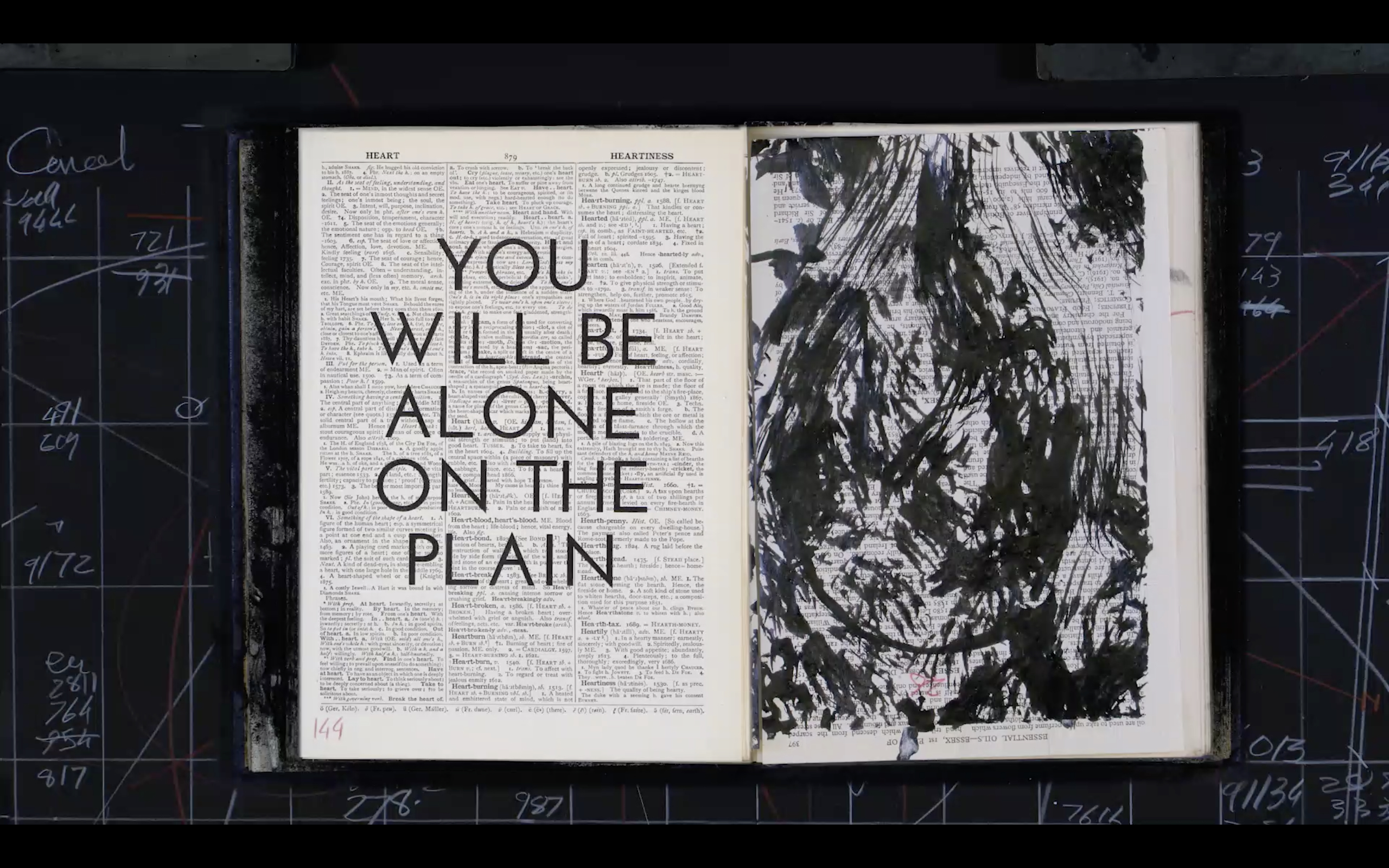

Excerpt from Felix in Exile, 1994

CURIOUS

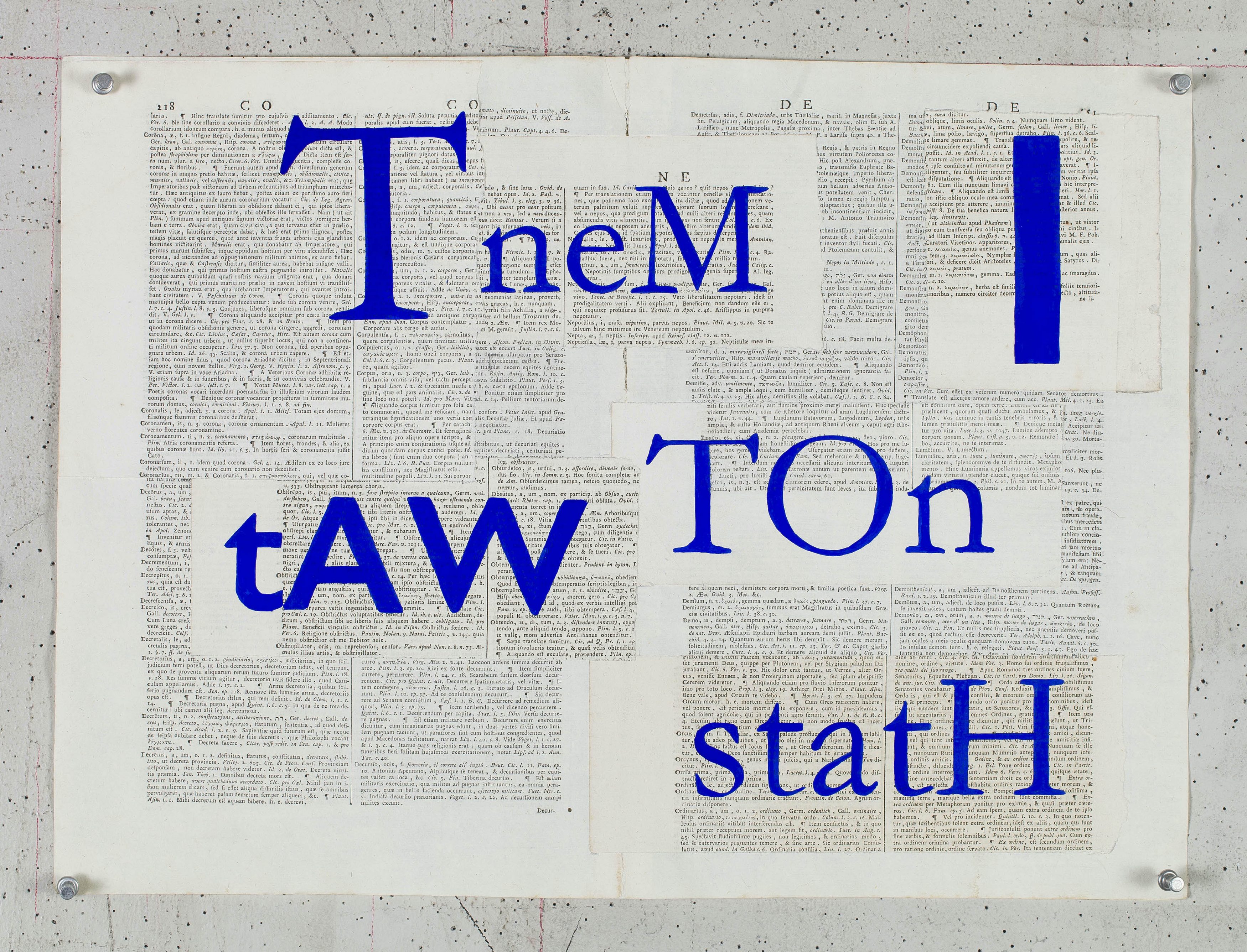

An essential quality of an artist is to have an openness to devour the world.

Excerpt from Lexicon – Greek/Latin 37″. Ref: 26/08/2010 (Drawing Lesson 45), 2010

KNOW

Walking, thinking, stalking the image. Many of the hours spent in the studio are hours of walking, pacing back and forwards across the space gathering the energy, the clarity to make the first mark. It is not so much a period of planning as a time of allowing the ideas surrounding the project to percolate. A space for many different possible trajectories of an image, of a sequence to suggest themselves, to be tested as internal projections. This pacing is often in relation to the sheet of paper waiting on the wall. As if the physical presence of the paper is necessary for the internal projections to seem realisable. The physical size and material enforces a scale, a particular stating point, a comparison. The myriad of possibilities is called to order. This pacing is sometimes ten minutes, sometimes a morning. (And the pacing is sometimes replaced by sharpening of pencils, gathering of materials, hunting for just the right music – all different forms of productive procrastination.)

Excerpt from Shadow Procession, 1999

DOUBT

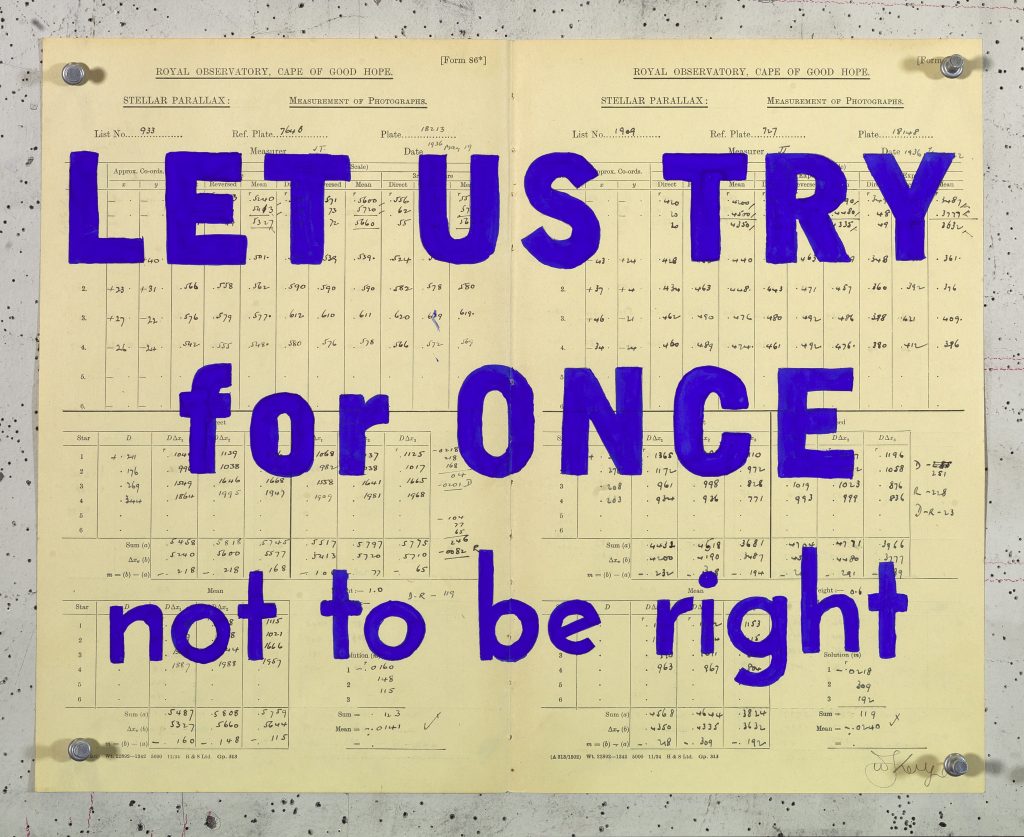

My work is about the provisionality of the moment. I’ve become very suspicious of certainty. First comes understanding the value of doubt. For me, that’s how we go through the the world.

Excerpt from Carnets d’Egypte: Shards 3’55”. Ref: 19/06/2010 (Drawing Lesson no. 43), 2010

COURAGE

When I was three years old, I was asked what I wanted to be when I grow up. I am reported to have answered that I wished to be an elephant. When I was fifteen, asked the same question, I replied that I wanted to be a conductor of operas. This longing was equally impossible. It was pointed out to me that to be a conductor of operas one had to read music. “Oh,” I said, “Yes of course.” I had to recalibrate. In the end directing operas was as close as I would get to either of those desires.

Video still from Sibyl, 2019

PLAY

And of course, in addition to all of this, as an artist one needs to work hard. No. Strike that. To play hard!

Tabletop Picnic for Rats, video fragment from studio work in progress, 2021

Words and images selected by Robyn Penn, June 2021